|

Results From the First National Assessment of HUD Housing

April 1999

Executive Summary

The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) spends $15 billion per year to subsidize 44,000 properties that are home to more than 4 million families and seniors. This includes $6.1 billion annually for 14,000 properties operated by 3,400 local public housing authorities and $8.3 billion annually for about 22,000 properties receiving project-based Section 8 or other forms of HUD rental subsidy. Another 8,000 properties benefit from FHA insurance or other forms of HUD assistance that do not involve direct rental subsidies. Despite this enormous investment of public funds, the Federal Government has never, since the inception of these programs-which have been in place for decades-had the ability to assess the condition of the properties supported by these funds. The failure to establish a system of uniform testing of the physical and financial condition of HUD subsidized properties has eroded the public trust by risking taxpayer dollars and failing to ensure decent, safe, and sanitary housing for the residents.

When Secretary Andrew Cuomo took office in January 1997, he made rebuilding the public trust his top priority. Within 6 months, he released the HUD 2020 Management Reform Plan, designed to repair the many management deficiencies which had troubled HUD over the years. Outside observers have validated HUD's reform efforts. Following a thorough review, management expert David Osborne wrote, "Taken as a whole, the HUD 2020 Management Reform Plan, as it is being implemented today, represents one of the most ambitious, fundamental, and exciting reinvention plans in the recent history of the Federal government." The Department's implementation has lived up to its ambitious plan. HUD has moved forward with its reforms at a rapid pace. The reforms already have begun to pay dividends. A report on the Department's progress by Booz-Allen & Hamilton showed, "HUD has made significant progress towards achieving the many management reforms that are critical to making the Department function effectively."

A central element of the HUD 2020 plan was the establishment of a Real Estate Assessment Center (REAC) to perform comprehensive testing of the quality of HUD housing. Last year, utilizing state-of-the-art technology and a carefully designed system of performance indicators, REAC began the process of conducting the first-ever complete inspection and assessment of Federally subsidized housing. By the end of the first quarter of 1999, REAC had inspected over 4,000 multifamily properties and 750 public housing authorities (PHAs). At its current pace of 100 to 200 inspections each day, REAC is on track to complete inspections of all 44,000 HUD subsidized properties by year end. This report presents a review of results from REAC's initial inspections and other monitoring. Included are the first data on the physical and financial condition of public housing, and the groundbreaking national survey of public housing residents.

Key findings of the report include:

- The vast majority of properties are in good physical condition. Overall, the first inspection results show that more than 80 percent of public and multifamily housing properties are in good or excellent physical condition. Physical inspection scores for the public housing authorities analyzed so far rank 87 percent as successful or high performers. Results for the multifamily housing properties inspected to date show that 83 percent are in good or excellent condition.

- Residents are satisfied with public housing. Perhaps the most encouraging results so far are from the first national survey of residents of public housing, which has just been completed. When asked how they felt about their public housing overall, 75 percent responded that they were satisfied or very satisfied with their dwelling units, while over 60 percent said they were satisfied or very satisfied with their development and their neighborhood. Almost 75 percent felt safe in their units day or night, although this dropped to about 50 percent when asked if they felt safe outside their buildings. Finally, 64 percent of residents said they would recommend their public housing development to a friend or family member, more than three times the number who said they would not.

- Properties everywhere are in good condition. In the region that includes the Northeast and Midwest, 73 percent of the buildings scored in the good or excellent range. The regions that cover the Southeast and West had even higher scores, with 87 percent and 82 percent, respectively, in good or excellent condition.

- Elderly and disabled housing is in the best condition. Early results indicate that properties built for the elderly and disabled under HUD's Section 202 and Section 811 programs are in the best condition, with almost 90 percent ranked in good or excellent condition.

- Typical problems were minor. The most commonly reported defects in the early inspections were minor problems in the dwelling units, including a need for repair or painting of the walls or ceilings; damaged floors, countertops, or cabinets; and a need for repairs to walkways and parking lots. The most frequent serious deficiencies were damaged fixtures or appliances, and plumbing leaks, in the kitchens and bathrooms.

Now, for the first time in its history, HUD will have complete and reliable information on the quality of housing it funds. With help from REAC, HUD can focus its resources on improving the most troubled properties. HUD must rebuild the public trust, however, by refusing to subsidize multifamily properties in poor condition or stand by as troubled housing authorities don't improve. At the same time, HUD can reward the best properties and housing authorities now that it knows which ones they are. But ultimately, REAC and the reforms it ushers in will help two groups the most. First, taxpayers will finally know that the funds they entrust to HUD are well spent. Equally important, the families and seniors meant to benefit from HUD's programs will now be sure of the decent homes they deserve.

I. Sorting the Good Apples From the Bad

For too many years, HUD betrayed the public trust. Charged with directing billions of dollars in taxpayer funds to the neediest Americans, the Department could not adequately account for how the funds were spent and whether they actually improved lives. Ultimately, it was the families and seniors meant to benefit from HUD's programs who suffered the most: As public confidence in HUD's competence shrank, so did funding from Congress.

Most devastating was the perceived quality of HUD housing. Across the country, news reports highlighted dire conditions and rampant crime in the worst of subsidized housing. These examples led to terms such as "warehouses for the poor" and "vertical slums," and ultimately to an indictment of the Nation's housing policy itself. Defenders of HUD's mission argued that the highly publicized cases featured a small fraction of the whole, and did not fairly represent the benefit HUD provided to the most vulnerable Americans. In essence, they argued, a few bad apples were allowed to spoil the whole bunch. The root of the problem, however, was that HUD could not show who was right-monitoring was weak enough that HUD couldn't tell the good apples from the bad.

The problems with HUD monitoring resulted from a number of weaknesses:

- Too little evaluation. The most basic flaw in HUD's monitoring was simply that the agency did not do enough of it. For example, properties receiving project-based Section 8 subsidies are required to have an inspection and submit an audited financial statement each year. Yet studies consistently showed that these standards were not met.

- Limited scope of evaluation. Even where HUD effectively evaluated certain aspects of performance, the scope was usually incomplete-HUD looked at a narrow range of indicators that didn't reflect a full picture of the housing's quality. Take, for example, the Public Housing Management Assessment Program (PHMAP), an assessment process required by the National Affordable Housing Act of 1990 to monitor and evaluate the management of public housing agencies. While PHMAP was designed to focus on the essential aspects of PHA management, it did not provide a standardized, independent assessment of the physical condition of the properties. Perhaps the most significant piece missing from HUD monitoring, however, was the lack of any input from the residents of HUD housing about what they thought of their communities. How can HUD be sure it is delivering quality housing without knowing what the people intended to benefit from the programs think?

- Inconsistent Criteria. Another flaw in HUD evaluation has been a lack of consistent criteria. With 44,000 public and multifamily housing developments spread throughout the country, effective monitoring requires a standardized set of criteria and factors that would allow meaningful comparisons to be drawn between the quality of housing in different places. Yet this has not been the case. For example, it was possible that an inspector of a multifamily property in one part of the country might deduct points on an inspection if the grass was not regularly cut, while another might deduct points only if there was no grass at all.

- "One-Size-Fits-All" Oversight. Another reason HUD has done too little oversight is that it did little to prioritize the properties that needed the most attention. Historically, nearly all HUD properties have been evaluated with the same frequency and intensity. Because HUD couldn't tell the good apples from the bad, it had to treat all properties the same: With limited information on the relative performance of different properties, little attempt could be made to relieve high performers of reporting burdens. Without this relief for high performers, HUD staff was stretched too thin with traditional "one-size-fits-all" monitoring to effectively help the troubled properties that needed it most.

II. A New HUD: The Real Estate Assessment Center

When Secretary Cuomo took office in January 1997, he made rebuilding the public trust his top priority. With precise focus, HUD began the task of putting its own house in order. Drawing upon the best public- and private-sector management approaches and calling on teams of HUD employees from all parts of the organization, the Department worked until June 1997 to create the HUD 2020 Management Reform Plan, a comprehensive strategy to reform the way HUD delivers programs and services to America's communities.

Outside observers have validated HUD's reform efforts. Following a thorough review of HUD 2020, management guru David Osborne wrote, "Taken as a whole, the HUD 2020 Management Reform Plan, as it is being implemented today, represents one of the most ambitious, fundamental, and exciting reinvention plans in the recent history of the Federal government." The Department's implementation has lived up to its ambitious plan. HUD has moved forward with its reforms at a rapid pace. The reforms already have begun to pay dividends. A report on the Department's progress by Booz-Allen & Hamilton showed, "HUD has made significant progress towards achieving the many management reforms that are critical to making the Department function effectively."

A critical part of HUD 2020 reform was an expanded ability to monitor the quality of HUD housing. And while the strategy to accomplish this part of the reform effort included a number of innovations, the linchpin was the creation of the Real Estate Assessment Center (REAC). REAC's mission was to centralize the monitoring of HUD subsidized housing into a single, state-of-the-art organization, with the expertise and resources to correct the shortcomings of HUD's earlier approach. With the assistance of partners representing public housing authorities and multifamily housing organizations, as well as HUD subsidized housing residents, housing advocacy groups, local governments, and other interest groups, REAC set out immediately to design the new monitoring systems. Experts in the fields of finance, audit, and physical inspection were instrumental in developing the new systems.

Less than 2 years after completion of the HUD 2020 Management Reform Plan, REAC and its systems have not only been created, they are improving the quality of HUD housing. Highlights of REAC's accomplishments so far include:

- Baseline inspection of all properties on track. This year, for the first time in history, REAC will enable HUD to inspect and score all 44,000 public and multifamily housing properties. Already more than 10,000 properties have been inspected since October 1998. Each day another 100-200 inspections are completed, putting REAC on schedule to complete the initial baseline inspection of all properties by the end of calendar 1999. This is the first major step in reversing the old pattern of insufficient monitoring.

- Comprehensive evaluations underway. To complement the progress on physical inspections, REAC is also implementing the other parts of its comprehensive monitoring systems. On the public housing side, REAC has established the Public Housing Assessment System (PHAS). In addition to the physical inspection, PHAS will review three other components: financial management, management operations, and resident satisfaction. Similarly, REAC will be looking at the financial condition and resident satisfaction of multifamily housing in addition to the physical inspection. To examine the financial condition of public housing authorities and multifamily housing owners, REAC has established uniform standards for annual financial reporting using standard business accounting principles. Public housing authorities and multifamily housing owners will be required to submit financial reports electronically and in a standardized format. Collection and analysis of financial statements is already underway. For the management operations component of PHAS, HUD will continue to measure the 22 management criteria included in the Public Housing Management Assessment Program (PHMAP), including vacancy rates, uncollected rents, completion of emergency work orders, lease enforcement, resident involvement, and numerous others.

- Resident input being gathered. As a crucial component of the comprehensive approach to monitoring, resident input will be included for the first time as an integral component in the evaluation of HUD housing. Residents will be asked their opinion of the quality of their apartments, resident organizations, program activities, safety, and other issues. REAC recently completed a pilot for the public housing resident survey, and the multifamily housing version will be implemented soon.

- Standardized criteria used for all monitoring. HUD believes that all its housing, regardless of the subsidy or assistance source, should be assessed using uniform physical condition standards. The REAC, with assistance from its public and multifamily housing partners, established these uniform physical and financial standards. The physical inspection protocol covers all facets of Housing Quality Standards (HQS), including 60 types of items to be inspected and about 400 potential deficiencies. It is designed to be objective in identifying and classifying these deficiencies, providing more reliable results than in the past. Now, for example, REAC inspectors across the country who find a hole in the wall of an apartment or a leak in a pipe will use the same guidelines on how to score the problem based on the size of the hole or the severity of the leak. With consistent criteria defined for each possible defect, HUD can be sure that its grades for housing quality really mean what they say.

- State-of-the-art technology speeds monitoring. A key aspect of the new monitoring systems is the advanced technology that allows faster and more accurate work by HUD staff. This technology has fundamentally transformed the old way of doing business. When a HUD inspector visits a property, for example, the inspector will now use a special hand-held computer, known as a data collection device (DCD), to record the assessment. This device randomly chooses the units to be inspected on the date of the visit, and also allows digital photos of the property to be taken and included with the inspection report to remove any uncertainty about what the inspector actually saw. After the inspection is completed, data from the DCD is downloaded to HUD via the Internet to the central information data repository, which automatically calculates the score.

- Quality checks of the REAC process key to success. To ensure the most accurate evaluation system possible, HUD even grades the graders. Each score is run through a rigorous set of reviews to check for any anomalies before the report is released to the PHA or owner. In addition, REAC is conducting regular follow-up inspections to confirm the accuracy of the originals, thereby ensuring the integrity of the evaluation process.

III. Initial Results Show Good News

With implementation of the new monitoring systems well underway, initial data from REAC physical inspections show encouraging results:

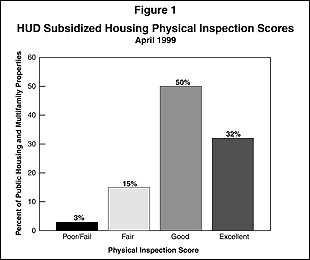

- The vast majority of properties are in good physical condition. The first results from REAC indicate that HUD subsidized housing is in very good condition, reinforcing the belief that troubled properties make up a small portion of the 44,000 properties HUD assists. Overall, more than 80 percent of public and multifamily housing properties are in good or excellent physical condition: One-third of properties inspected received excellent ratings, while one-half were rated good. In contrast, 15 percent of properties inspected received fair ratings, while less than 3 percent were in poor or failing condition. (See Figure 1.)

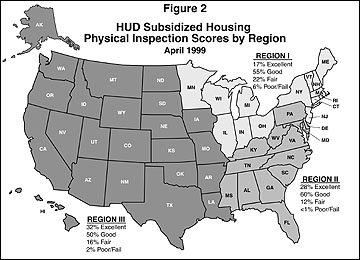

- Properties everywhere are in good condition. While there is some variation geographically, HUD subsidized housing is in good condition in all regions of the country. In the region that includes the Northeast and Midwest, 73 percent of the buildings scored in the good or excellent range. The regions that cover the Southeast and West had even higher scores, with 87 percent and 82 percent, respectively, in good or excellent condition. (See Figure 2.)

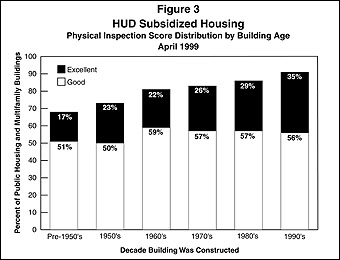

- Older buildings and harsher weather lower scores in the Northeast and Midwest. In part, the lower scores in the Northeast and Midwest are explained by the fact that properties in these areas are generally older. Figure 3 shows that the share of buildings in good or excellent condition declines directly with the age of the housing, a result which is not surprising given that everything, including buildings, wears out over time. Therefore, the older age of the buildings in the Northeast and Midwest-28 percent of the buildings were built before 1960-helps explain why there are fewer buildings in good or excellent condition than in the Southeast and West, where only 21 percent and 16 percent of the buildings, respectively, were built before 1960. Interestingly, the results also appear to show that buildings age faster in the Northeast and Midwest and slower in the Southeast. Scores in the Southeast drop consistently with the age of the building, from 91 percent good or excellent for properties built this decade to 83 percent for properties built in the 1950's. In the West, scores also drop consistently with age, but from the same 91 percent good or excellent for properties built this decade to 72 percent for properties built in the 1950's. In the Northeast and Midwest, the condition of properties drops even more quickly as buildings age-from 91 percent good or excellent for properties built this decade to 57 percent for properties built in the 1950's. The most likely explanation for the quicker decline of buildings in the Northeast and Midwest is the damage caused by more severe weather.

- Typical problems were minor. The most commonly reported defects in the early inspections were minor problems in the dwelling units themselves, including a need for repair or painting of the walls or ceilings, and damaged floors, countertops, or cabinets. A need for repairs to walkways and parking lots was also a common finding. Looking just at more serious deficiencies, the most frequent were in the kitchens and bathrooms-damaged or inoperable fixtures or appliances, and plumbing leaks.

Public Housing

As described above, the new PHAS evaluation system for public housing authorities (PHAs) has four components: physical condition, financial management, management operations, and resident satisfaction. As the system is fully implemented, all four areas will be evaluated and a numerical score assigned to each. The first three categories are each worth 30 percent of the total score, and the last category is worth 10 percent. Based upon the total score, a PHA will be designated as either a high performer, successful performer, or troubled performer. Early results show the large majority of PHAs are doing a good job.

Multifamily Housing

Thus far, results for HUD's multifamily housing-which includes 30,000 properties that are insured by FHA or assisted by project-based Section 8 and other subsidies-have been limited to physical inspection scores. This is because, unlike PHAs, nearly all owners of multifamily properties report financial results on a calendar year-end basis. This means that audited financial statements are just beginning to arrive at REAC and the first combined scores for multifamily properties will not be available until this summer. Nonetheless, final physical inspection scores are available for over 10 percent of the multifamily universe, and the results so far are encouraging:

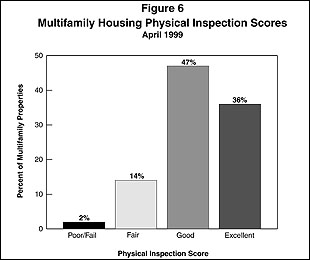

- HUD multifamily housing is in good physical condition. Overall, 83 percent of multifamily housing properties are in good or excellent condition. Over one-third of properties received excellent ratings, while almost one-half were scored as good. In contrast, less than 15 percent of properties received fair ratings, while a tiny group of 2 percent were judged to be in poor or failing condition. (See Figure 6.)

- Elderly and disabled housing is in the best condition. Early results indicate that properties built for the elderly and disabled under HUD's Section 202 and Section 811 programs are in the best condition, with almost 90 percent ranked in good or excellent condition. Properties subsidized by project-based Section 8 are also in very good condition-more than 80 percent ranked in good or excellent condition. Only multifamily properties with mortgages held by HUD showed significantly worse results-30 percent were in fair or poor/failing condition. This result is not surprising, however, given that HUD only takes control of mortgages on properties that are physically or financially troubled.

- Resident survey will complete the picture. Now that REAC has completed the pilot resident survey for public housing, a similar pilot will be undertaken for HUD multifamily housing. When combined with the results of the physical and financial scores, the survey will give HUD a truly comprehensive picture of the quality of HUD insured and assisted housing.

IV. Rewarding the Good and Improving the Bad

Now that HUD is beginning to have complete and reliable information on the quality of housing it subsidizes, HUD can use the information to do a better job in enforcing high standards at bad properties and regaining the public trust. But this is not enough-HUD must use the information to work smarter as well as better. In the past, because HUD couldn't tell the good apples from the bad, it had to treat all properties the same. With complete and accurate data from REAC, this is changing.

- Rewarding the good properties. By using the REAC ratings to shift its oversight away from good buildings and onto the poor performers, HUD can do more with less-decreasing the burden on its staff and encouraging good buildings to continue performing well. On the public housing side, housing authorities that are ranked as high performers will benefit from streamlined planning requirements, bonus points in applications for competitive funding, and other rewards. On the multifamily side, the best-performing owners and managers will also benefit from their strong track records. One example is the inspections themselves: If a property is maintained in good condition, HUD will inspect it less often than the current annual requirement. Those in poor condition, however, will get closer scrutiny.

- Taking action against the bad properties and bad owners. Actions are already being taken against properties whose results from REAC show reason for concern. First, any health and safety issues identified during inspections are communicated to PHAs and multifamily owners on the spot, along with requirements to fix the problems within specified time periods. Serious health and safety deficiencies or fire safety hazards must be corrected immediately, since the safety and well-being of tenants may be in peril. Requirements for health and safety concerns are independent of the overall score a PHA or multifamily owner receives-the deficiencies must be corrected no matter how good the general condition of the property.

If a PHA is rated a troubled agency, the PHA is referred to one of the two recently established Troubled Agency Recovery Centers (TARCs). Using specialists in financial management, housing operations, budgets, personnel, and resident relations, the TARCs will work with troubled agencies to improve performance and help them meet HUD's new standards. If PHA problems are not resolved within a 1-year time limit, the PHA will be referred to HUD's newly created Enforcement Center. However, if a PHA has made substantial progress, demonstrated by a 50 percent improvement in score, then the PHA can be allowed to continue the recovery effort. The Enforcement Center (EC), established at the same time as REAC, is responsible for enforcement activities on the most troubled HUD subsidized properties. Actions taken against failing housing authorities by the EC can include judicial receivership to remove failed management and, where appropriate, civil and criminal sanctions.

On the multifamily housing side, a similar intervention strategy has been developed. If the property is rated in fair condition and the repairs cannot be completed within 90 days of the inspections, the owner must work with HUD's multifamily field offices to develop a detailed repair plan. These high-risk properties will be referred to one of more than 100 Senior Troubled Project Managers, a group of highly qualified and experienced staff established to improve conditions at troubled projects around the country. With the help of REAC, they are focusing on early warning signs with the goal of improving affordable housing before it becomes troubled. If, however, a property becomes seriously troubled, indicated by a rating of poor/fail, the property is referred to the Enforcement Center for evaluation of whether enforcement actions are in order.

V. The Rapid Pace of Reform

Whether measured against public or private sector standards, REAC has been designed and implemented at a remarkable pace. By the end of 1999, HUD will complete inspections of all 44,000 of its public and multifamily housing developments. Last year, Pricewaterhouse Coopers reviewed the critical performance milestones for HUD's 2020 Reform Plan and "found that implementation of the Community Builders, Enforcement Center, Procurement Reform, Real Estate Assessment Center, Storefronts, and Troubled Agency Recovery Centers, is well underway. Each project met all or substantially all of the critical milestones that HUD established for completion as of September 1."

With REAC, HUD is restoring the public trust. The Department is learning vital information about its housing stock and has a system in place to act on that information. REAC will help improve housing conditions for thousands of families and seniors from coast to coast through tough and consistent application of rigorous standards. REAC is critical to HUD's efforts to get its own house in order-and it's working. Booz-Allen, among others, thinks 2020 Reform is a success: "These reforms, when implemented, should present a significant improvement in HUD's performance; lower the risk of fraud, waste, and abuse in its programs; and position the Department to better serve America's communities."

Content Archived: January 20, 2009

|